Employee Experiences with an ERP Implementation: Monitoring Employees

Continuing with my blog post series on my research with employee experiences with ERP implementations, I’ll review the fourth recommendation made for company leadership undertaking these projects. The objective of this research was to understand employee experiences with ERP implementations and whether there are factors related to retention and satisfaction that companies should be mindful of during that process.

For reference, the three recommendations made in this series so far have included:

- Recommendation 1 - Recognize that ERP transformations re-design jobs, and proactively maintain or add elements to jobs that are intrinsically motivating.

- Recommendation 2 - Ensure that excellent project management skills are practiced throughout the implementation process.

- Recommendation 3 - Provide mechanisms for employees to participate with, and provide input on, the project and related decisions.

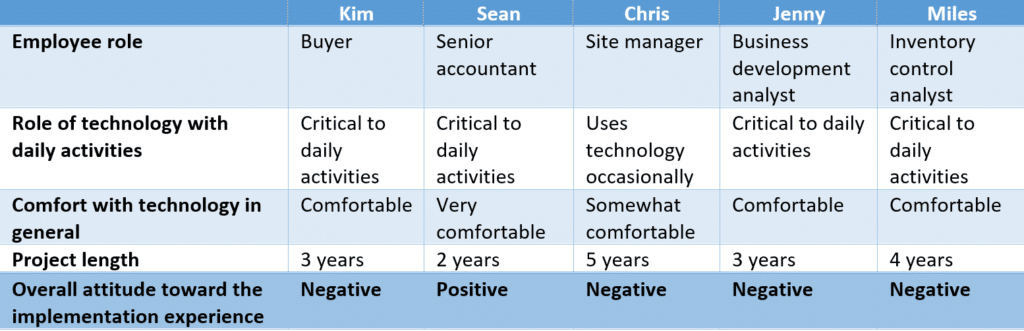

With the five sets of employee experiences that were gathered, I continue on to the next recommendation:

Recommendation 4:

Ensure employees continue to have access to adequate personal, material, and social resources as the implementation process inevitably increases their workload. Closely monitor indicators of employee burn-out and disengagement.

Throughout my interviews, participants frequently spoke of hardships endured from operational disruptions, material disruptions, and availability of resources introduced by their implementation projects.

When her company went live on their new system, Kim described having to work long hours, nights, and weekends simply to keep up with the increased daily workload. She described how her department’s attitudes were negatively affected by the resulting reduction in productivity for their team. In another interview, Chris, having been assigned additional responsibilities for employee readiness training for their new system, described feeling overwhelmed with what was expected from him, eventually leading to him actively pursue other employment. He described this experience:

“It was hard to keep the momentum up because it felt I was doing two jobs: trying to make sure everyone was trained and we had all of our needs taken care of, while still trying to make sure the day-to-day activities were covered… I think it was hard on a lot of people, even on those [who weren't involved with the project] because all of the work trickled down while everyone else was taken away for training or testing.”

Miles echoed this theme through his description of the frustration he felt regarding having to set aside projects and improvement initiatives due to the priority given to the implementation project. He found it difficult to get people and resources to help him manage his increased job demands, and found support for their current system to be strained:

“It was a running joke that when we were met with a problem that we needed to [address], that we're "on a code freeze," and we're not going to get resources to resolve [the problem]… Any project in the company needs a code change, and it was a running joke… If any change initiative that we want to make happen to the process requires a code change, it's not going to happen.”

He described that this negatively affected his job satisfaction because he continued to see areas that needed improvement and attention, but had little time or opportunity to address them. He continued by describing how the implementation project affected him personally:

“Being frustrated at work will bleed into your personal life. It’s easy to have a short temper at home or to have less patience at home. Or even due to the lack of resources, having to put in extra time or hours at work means less time with the family.”

Jenny, in another interview, felt overwhelmed with the need to balance her project responsibilities with her everyday workload, resulting in her feeling that her work attitude had suffered substantially:

“The project drained people, there was a definite shift in attitudes which was hard. Particularly for the finance group... having to manage more than their jobs... we [consistently] had to draw more lines to pull in people. Because we were too overburdened to test and contribute, which doesn't help [the success of the project]… We would put in all of this time, throw more people in it, and have to keep going at it like nothing happened. It's not sustainable.”

She further echoed how the time commitments of her project affected her personal life due to policies that her company made which restricted vacation use during training and go-live events. Kim and Sean both described their managers being less available due to the time required of them on the implementation teams. Kim associated this with a feeling of loss in terms of not having someone to go to or having “someone in [her] corner,” and felt her team lost some cohesiveness as a result. Sean’s team had to put in extra hours to cover the responsibilities that his manager and controller were not able to handle, and further reported they remain understaffed in his department.

These experiences collectively illustrate the negative effects felt from changes in employee resource adequacy, personal impacts, and time commitments.

Ensure Impact Felt from the Project on Daily Operations is Kept to a Minimum

Personal and material resource theory describes how constraints on an employee’s abilities or opportunities to achieve their work goals are demotivating.1 The availability of these resources, in the form of personal, material, and social resources, has a direct and significant effect on an employee’s perceived level of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and thus has an indirect impact on employee morale and work commitment.

Simply put, an employee’s perceived level of resource adequacy leads to their perception that they have the means needed to perform their work successfully.2 This can range from feeling they possess adequate time and tools to complete their assigned tasks, to having the freedom to step away when they feel overwhelmed. Their perceptions of resource adequacy are therefore likely to either strengthen or weaken their development and feelings of intrinsic motivation. Pushed to the extreme, constraints on these perceptions can eventually lead to decreased motivation, indifference, and learned helplessness.

Research has revealed that employees’ perceptions of human resource practices related to working conditions, in the context of skills and available resources, are a significant predictor of their level of engagement.3 The recommendation here is to ensure that the impact felt from the project on daily operations is kept to a minimum by continuing to provide employees access to the same level of personal, material, and human resources as they did prior to the project, while closely monitoring indicators of employee burn-out and disengagement. This recommendation encompasses both the themes of resource adequacy concerns and personal and time commitments as they are intrinsically related.

Avoid a Tug-of-War Over Resources

Leadership should be aware of the potential need to increase staffing prior to go-live to address any future-state departmental processes and reduced efficiency that will likely occur; unexpected changes to an employee’s work schedule, intensity, and ability to perform their jobs have been found to contribute to increased job stress and turnover rates.4 Furthermore, leadership should expect a substantial increase in work intensity and difficulty after go-live while issues get ironed out and people become more accustomed to the technology.5 Having resources trained and ready will better equip companies to be effective throughout the project, rather than creating burn-out for existing employees who are trying to achieve the same levels of performance they had with their old system.

More importantly, PTO or vacation “blackout” policies should be carefully considered as they are likely to have a harmful effect on employees’ perception of the organizational culture -- the set of beliefs, values, and behaviors shared by employees that enhance the quality and presence of employee engagement.6 In particular, factors that make employees feel valued and believe that their leadership cares about their health and well-being are clear antecedents to employee engagement.7

A potential tug-of-war over resources can occur when employees are needed for project planning and process discussions while everyday activities and operations are expected to continue. The recommendation, therefore, is to devote internal resources to the project while at the same time increasing staff levels to backfill their work tasks, or to depend on contractors and consultants in an increased capacity to handle project tasks and responsibilities. Although economic constraints are a consideration in implementing any form of a new technology system, the unseen social costs of implementation should be considered and integrated into budgeting and planning discussions.

References used in this research:

1Katzell, R. A., & Thompson, D. E. (1990, February). Work Motivation - Theory and Practice. American Psychologist, 45(2), 144-153.

2McAllister, C. P., Harris, N., J., Hochwarter, A., W., Perrewe, . . . Ferris, G. R. (2016). Got Resources? A Multi-Sample Constructive Replication of Perceived Resource Availability’s Role in Work Passion–Job Outcomes Relationships. Journal of Business and Psychology, 147-164.

3Aktar, A., & Pangil, F. (2018). The Relationship between Human Resource Management Practices and Employee Engagement: the Moderating Role of Organizational Culture. Journal of Knowledge Globalization, 10(1), 55-89.

4Woo, S. E., & Maertz, C. P. (2012). Assessment of Voluntary Turnover in Organizations: Answering the Questions of Why, Who, and How Much. (N. Schmitt, Ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Personnel Assessment and Selection, 1-42.

5Jones, D., Kalmi, P., & Kauhanen, A. (2011). Firm and employee effects of an enterprise information system: Micro-econometric evidence. International Journal of Production Economics, 130(2), 159-168.

6Robinson, D., Perryman, S., & Hayday, S. (2004). The Drivers of Employee Engagement. Brighton: Institute for Employment Studies.

7Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002, April). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268-279.

Further reading:

https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_orgdev_docdiss/72/

Under the terms of this license, you are authorized to share and redistribute the content across various mediums, subject to adherence to the specified conditions: you must provide proper attribution to Stoneridge as the original creator in a manner that does not imply their endorsement of your use, the material is to be utilized solely for non-commercial purposes, and alterations, modifications, or derivative works based on the original material are strictly prohibited.

Responsibility rests with the licensee to ensure that their use of the material does not violate any other rights.